The Controversy Surrounding Parental Decision-Making: My Life Story

An insight into one of the most overlooked, but perhaps controversial, topics, regarding a parent’s child.

Some people say it’s wrong. Some say you shouldn’t have any control over any two sets of DNA that aren’t yours. That it’s immoral to pick and choose what ultimately becomes one of the most defining aspects of a child’s life, and with no consultation in their presence whatsoever. The ultimate question really boils down to this: Should young children have a say regarding the decisions that govern their body, especially when taking into consideration that these outcomes are the ultimate deciders of their future? In other words, should parents wield the power of making significant life-changing decisions for their child (who are seemingly too young to know any better)? In regards to the latter, I most certainly agree.

To conceptualize this, I like to think of life as being like a giant, yet intricate spider web: A complex system of silk-threaded strings, or paths, which connect the next spiral on the web to the one before it, and all of which emanate from a singular and central hub.

In this manner, one can think of these silk-threaded strings as being representative of, both literally and figuratively, different “paths” that one might take in their life. In other words, a spider web can essentially be thought of as like a sort of queue, or an entire domain, that represents all possible choices in one’s life, and all of which originate from one central moment in time — the creation of that being. Thus, for every path, or “choice,” taken on the web, one is effectively choosing against a set amount of other unique decisions (as every decision or action made naturally involves some sort of trade-off). While the number of these choices is, from a practical standpoint, technically infinite, the concept of the spider web serves to scale down the idea into comprehensible terms. As one moves further and further away from the hub that defines their existence (i.e., by making certain choices and taking different paths in their life), newer choices and decisions begin defining that instantaneous point and moment time.

This gets far more interesting, and perhaps even controversial, when you put parental decision-making into the picture. Since all decisions are irreversible as the arrow of time is perceived (by humans) to be one directional, it is easy to see the controversy regarding whether parents should be allowed to predetermine a child’s path on the so-called “web,” as that effectively terminates a wide variety of possibilities, and even futures, for that child. To put it more practically: For every neighborhood that parents might move their children into; for every school that they enroll them in; and for every curfew they administer — they are effectively guiding these kids into picking what becomes a far narrower, and far different, domain of choices.

Now, of course, such actions mentioned are considered quite uncontroversial in the grand scheme of things, but the story changes with the implementation of more heavily weighted decisions (weighted, in this context meaning that such a choice/decision has a much more lasting impact on that person’s life) such as life-changing procedures and operations. When parents consent to such dramatically life-changing operations, they are, from a figurative standpoint, effectively “removing” certain sections of that child’s life “domain.” This then brings one to wonder of the previously posited question— should parents even wield the power of making significant life-changing decisions for their children, and if so, is there a definite line that governs how much power parents hold?

Want to read this story later? Save it in Journal.

My name is Oscar Petrov.

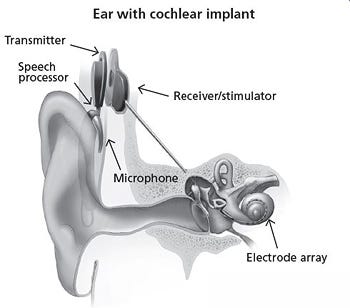

When I was 1 year old, I was diagnosed with congenital hearing loss. My sister, too, although she was 3 at the time. Not long after, my parents probably made one of the hardest decisions of their life—they gave the consent for the procedure to implant us both with a Cochlear Implant, an event that would ultimately affect us for the rest of our lives.

Looking back in time, I really wish that I could owe all of my success to my parents — whose resilience, determination, and unfettering love and support guided me all throughout my life. But it would be erroneous to simply give them all the credit. When I was younger—much, much younger—my parents sought help from an organization called Listen and Talk.

Listen and Talk was one of the few organizations dedicated to helping young children who are deaf and hard of hearing. It is to them that I must express my incredible gratitude for helping me when both of my parents were away — working hard to keep the refrigerator full, the electricity on, and the water running. It is to Listen and Talk, and its incredible staff members, that I owe my gratitude because of how much of an influence they had in helping me to become who I am today.

Speaking of “today” …

Fast forward to now—16.

Every morning I wake up. I walk over to my desk where I unplug one of two batteries which I re-charged the night before and insert it into my electronic device. When the light flashes on, I put the device around my right ear and attach the magnet to a little spot on the side of my head. In less than a fraction of a second, I am magically able to “hear” sound, and then I carry on with my day.

Stop. Wait a minute. Let’s try this again.

Every morning I wake up. I walk over to my desk where I unplug one of two batteries that I plugged in to re-charge the night before. I twist the battery into place in my sound processor, a routine as instinctual as plugging a charger into your laptop. When the light flashes on, I then place the device around my right ear and attach the magnet to a little spot on my head. This process effectively establishes a connection between the sound processor (or, transmitter) atop my ear and the cochlear implant receiver in my head.

The sound processor, simultaneously, begins picking up sound from the nearby environment and instantly transmits it to the receiver. The cochlear implant then transmits this information to my brain by firing electrode signals via the auditory nerve; as a result, a world of absolute silence ultimately fades away for me, and I immediately “hear” sound.

A habitual, and simple routine, but nonetheless, a far overlooked one. It’s from there that I then go on to start my day — which often tends to involve turning on some 70s/80s Rock Classic songs by any of my favorite bands: Aerosmith; Nirvana; REO Speedwagon; Scorpions; Foreigner; Black Sabbath; Led Zeppelin; Pink Floyd; Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers; Poison.

I mention the prior because it has come to my realization that I often overlook the significance of my device and it’s functions; I often overlook the origins of the cochlear implant, which dates all the way back to the 1960s; I often overlook the science behind the device and its workings; the people who helped me when I needed it most; I often overlook the fact that there are so many people in this world who aren’t as fortunate enough as I am to have a cochlear implant, and that my Cochlear Impact has had such a great impact on my life and in developing the 16-year-old that I see in the mirror each morning. The 16-year-old that loves playing chess competitively (at the state, national, and even international level), discussing philosophy Quantum and Mechanics—or more broadly, into metaphysics; Who loves hanging out with friends, playing Ultimate Frisbee for his school, collaborating with others on unique projects, and talking to and listening to people on a daily basis…

The 16-year-old that—

loves talking to and listening to people on a daily basis, none of which would have been possible without the help of my parents, the help of Listen and Talk, the workings of my surgeon, and, of course, my Cochlear Implant.

In the end, not a day goes by that I regret the choices that my parents made for me. At every moment throughout my life, while it may not seem so, I am so appreciative and thankful for the sound that reaches my brain but far more importantly, of everyone that worked so incredibly hard to get me where I am today.